This article first appeared in Mint as an opinion editorial on 31st March 2020.

Few days back Dr. Sara Cody, director of the Santa Clara County’s Public Health Department, US was speaking at a press conference about a simple, yet vital, way on how people can stop coronavirus from spreading: Don’t touch your face. “Today, start working on not touching your face — because one main way viruses spread is when you touch your own mouth, nose, or eyes,” Dr. Cody, said at the press conference. Less than a minute later, Dr. Cody brought her hand to her mouth and licked her finger to turn a page in her notes.

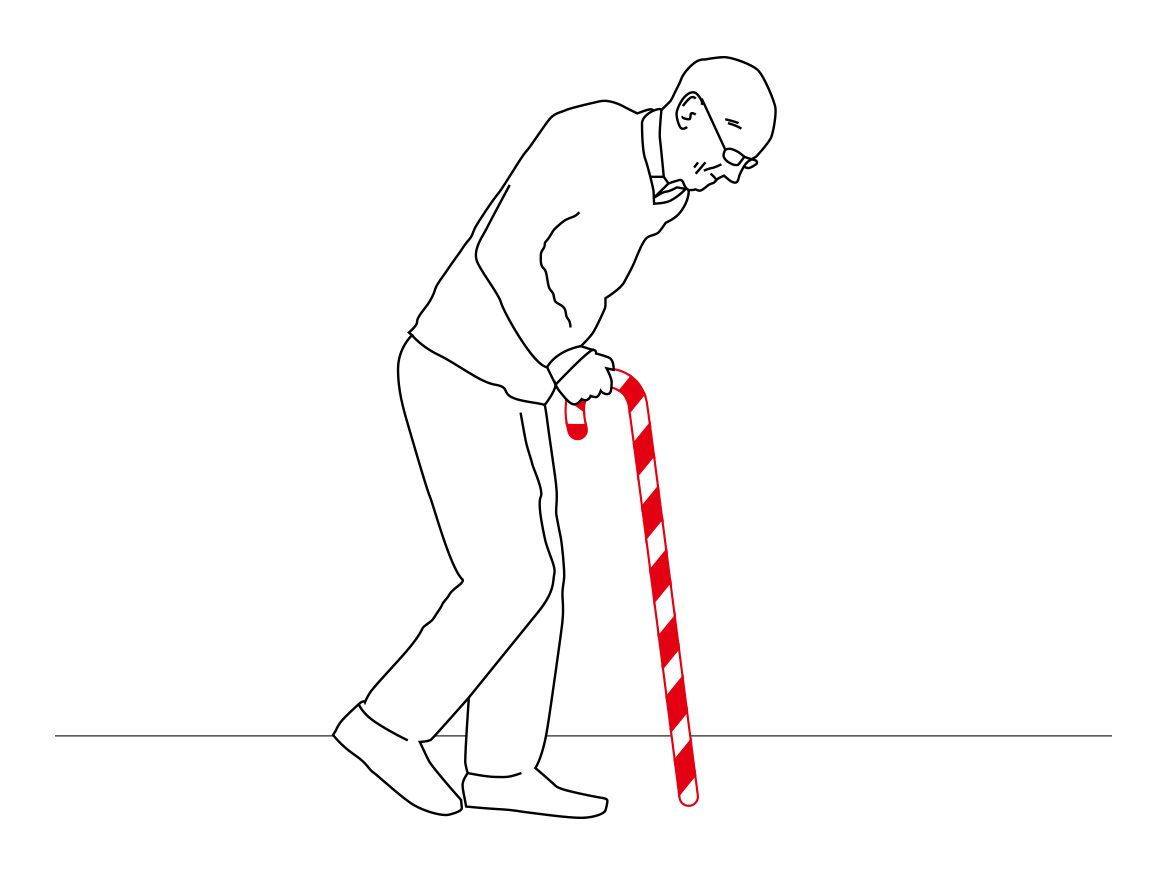

It’s not just Dr. Cody, millions have the habit of touching their tongue before turning the page of a document, especially the elders, who are at the highest risk of catching coronavirus. This is just one of the instances of touching a part of the face. The bigger problem is that almost every human being in the world has a habit of touching their face, including me and probably you too. A study by scientists in New South Wales, Australia, Kwok, Gralton and McLaws, found that on average people touch their faces 23 times an hour. What makes this behaviour tricky is that it’s a habit.

Habits are automatic behaviours that are done sub-consciously. They are actions that we perform frequently on auto-pilot. That’s precisely why they go unnoticed. This makes habits tricky because we aren’t even aware of it. Honestly this is the first time, being a behavioural scientist, that I’m even thinking about touching my face. I must be doing it all the time everyday without any realization whatsoever. But now we’re finding that coronavirus can spread easily, by touching surfaces that may be infected with the virus, and then touching any part of the face like mouth, nose or eyes – where the body’s mucous membranes are vulnerable to infection. That’s bringing up our habit of touching our face and making us aware of it. But even after being aware of it, I can’t help touching my face.

Ironically, the more you want to consciously avoid something, the more you think about it. So the more one thinks about not touching the face, the more it makes you want to touch your face. You are probably wanting to touch your face right now. That’s because you’ve been momentarily made conscious of your face, eyes, nose and mouth. This simple fact makes you want to touch it, perhaps as simple as scratch your cheeks a little or adjust your eyebrows or itch your nose. The other reason is psychological reactance. People cannot resist indulging in precisely what they’ve been told to avoid. It’s like being on a diet. When people are on particular diets and forbidden to eat certain foods, it makes them want to eat those foods even more.

Touching the face is an instinctive response. A recent study by behavioural scientists Mueller, Martin and Grunwald show that face touching is involved with coping with stress, regulating emotions and stimulating memory. Other researchers have established it’s an instinct we share with monkeys and apes. Gorillas, orangutans and chimpanzees all exhibit similar face-touching behaviour. But what can we humans do to prevent touching our faces and prevent getting infected this way by coronavirus?

Washing hands is the need of the hour. But we also need to use our hands often to open doors, press lift buttons, use keyboards, drink from glasses, use pens, open and shut taps, and a hundred other things that we don’t think about. How often can one wash hands or even use the hand sanitizer. It can be overwhelming if we have to wash hands after touching everything. I’m not recommending we don’t do it. I’m simply saying that it’s not practical to keep washing hands after each and every interaction.

Keeping our hands away from our face requires a lot of willpower. But willpower has been shown in behavioural science studies to always be limited in supply. Willpower works temporarily in the moment when one is conscious but wears out quickly as we slip back into doing things subconscious i.e. habits. Willpower is a bit like our muscles. The stronger our muscles are, the more we can work them out. But eventually they tire out. Similarly, the stronger our willpower is the more we can work them out but eventually we tire out. So willpower is not a dependable way of avoiding to touch our faces, while touching our face is going to be unavoidable.

That’s why we need to rely on behavioural design to help us not touch our face. Behavioural design is about tweaking our environment, right at the time and place our behaviour takes place, to achieve the desired action. For example, to reduce the quantity of food intake, instead of relying on willpower, if we reduce the size of the plate we eat from as well as the size of the spoon, we’re likely to eat less. Similarly, to avoid touching our face with our hands, we could try keeping a clean tissue at a close distance. By using clean disposable tissue we could prevent our bare hands from touching our eyes, nose and mouth. You can use a small portion instead of one whole piece to conserve paper. Small things make a big difference.