This article first appeared in afaqs, a leading Indian marketing and advertising publication. Afaqs shared it as a “mustread, brilliant article” on social media.

The mutual fund industry has been running an ambitious investor awareness campaign ‘mutual funds sahi hai’. At the same time, the AUM of the mutual fund industry touched a record level of Rs23 trillion by end of 2017—up from Rs16.46 trillion at the end of December 2016. But correlation does not mean causation. The main causes of the rise in mutual fund industry’s AUM is the combination of the effect of demonetization, decline in interest rate on fixed deposits, gold and real estate’s lackluster performance, flow of FII investment in Indian markets and the historical fact that retail investors are the last to jump into equity markets.

The ‘mutual fund sahi hai’ campaign has had messaging like ‘life mein risk, toh mutual funds mein kyon nahi’ (if there’s risk in life, then why not in mutual funds’), ‘thoda thoda karke bhi invest kiya ja sakta hai’ (one can invest small sums too), ‘planning long-term karni ho ya short-term’, ‘mutual funds mein patience rakhna zaroori hai (one needs patience in mutual funds). The campaign has poured crores of the industry’s money into such communication. However, the campaign reminds me of the story of the blind men and the elephant. According to the story, none of the blind men were aware of the shape and form of an elephant. So they inspected it by touching it. The blind man whose hand landed on the trunk, thought the elephant was like a thick snake. The one who touched its ear, thought it was like a fan. The one who touched its leg, thought it was like a tree-trunk. The one who touched its side thought it was like a wall. Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk and described it as a spear. None of the blind men had the complete context.

Similarly, the ‘mutual fund sahi hai’ campaign creates limited perception by describing ‘stand-alone features’ of a mutual fund. It doesn’t describe what a mutual fund is. Without the complete context, each blind man saw the elephant as something other than what it was. Likewise, without explaining what a mutual fund really is, how would a first time investor understand the concept of a mutual fund? And without understanding the concept of a mutual fund, how would a first time investor trust it?

Most investor awareness campaigns include heavy doses of complicated financial jargons like power of compounding, equity, debt, hybrid, etc. But these words are alien for first time investors. Plus, campaigns include wishful thinking like be a disciplined investor and execute goal-based plans. A behavioural science study by Fernandes, Lynch, & Netemeyer – a meta-analysis of over 200 financial programs on educating investors – has found that the largest effect any of them had was a mere 0.1%. Research amongst first time investors by Briefcase shows that the only thing they recall about mutual funds is ‘mutual funds are subject to market risks, please read the scheme documents carefully before investing’, without even knowing what it really means. Leave alone the cognitive challenge of choosing a fund from over a thousand of them, they don’t even get the concept of a mutual fund. The ‘mutual fund sahi hai’ campaign doesn’t address this problem.

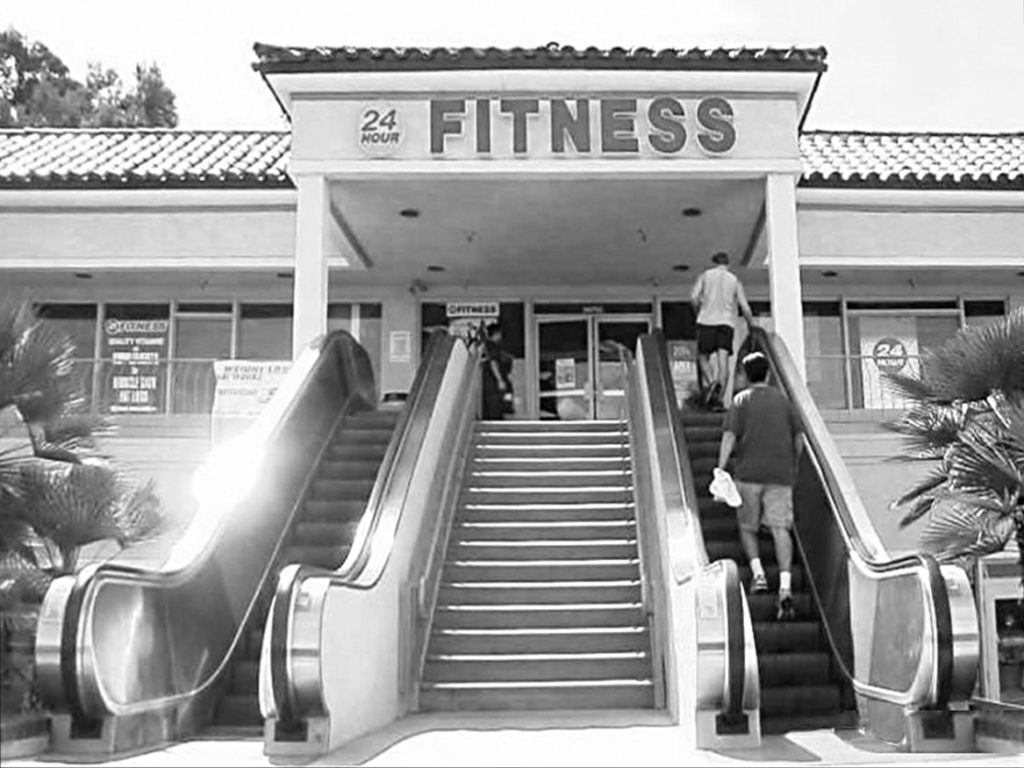

But behavioural science can help. Behavioural science involves using powerful principles to create intuitive communication. One example is the principle of familiarity. In an experiment by behavioural scientist Bornstein et al, faces of individuals were flashed on a screen so that quickly that participants couldn’t recall having seen those people. Yet, when these participants met those people, they liked them and were persuaded by them to a greater extent. So to get first time investors to adopt mutual funds faster, the communication needs to make the unfamiliar, familiar. Mutual funds need to draw heavily from what people are already familiar with – banks, savings, fixed deposits, recurring deposits, provident funds, etc. But the latest ‘mutual fund sahi hai’ campaign does exactly the opposite and talks about mutual funds being a new way of investing.

The behavioural science principle of cognitive overload shows that too much choice and information results in indecision and lower sales. Behavioural scientists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper set up a display at a supermarket in which passersby could sample a variety of jams that were made by a single manufacturer. Either 6 or 24 flavors were featured at the display at any given time. Results – only 3% of those who approached the 24-choice display actually purchased any jam. In comparison 30% bought when the choice was between 6 flavors. In an experiment on retirement funds, behavioural scientists Sheena Iyengar, Huberman and Jiang analyzed retirement programs of 8,00,000 workers in the US and found that when only 2 funds were offered, the rate of participation was around 75%, but when the 59 funds were offered, the participation rate dropped to about 60%. Likewise, the concept of mutual funds needs to be made simple and easy to understand, without any jargons, ensuring there’s no cognitive overload for first time investors.

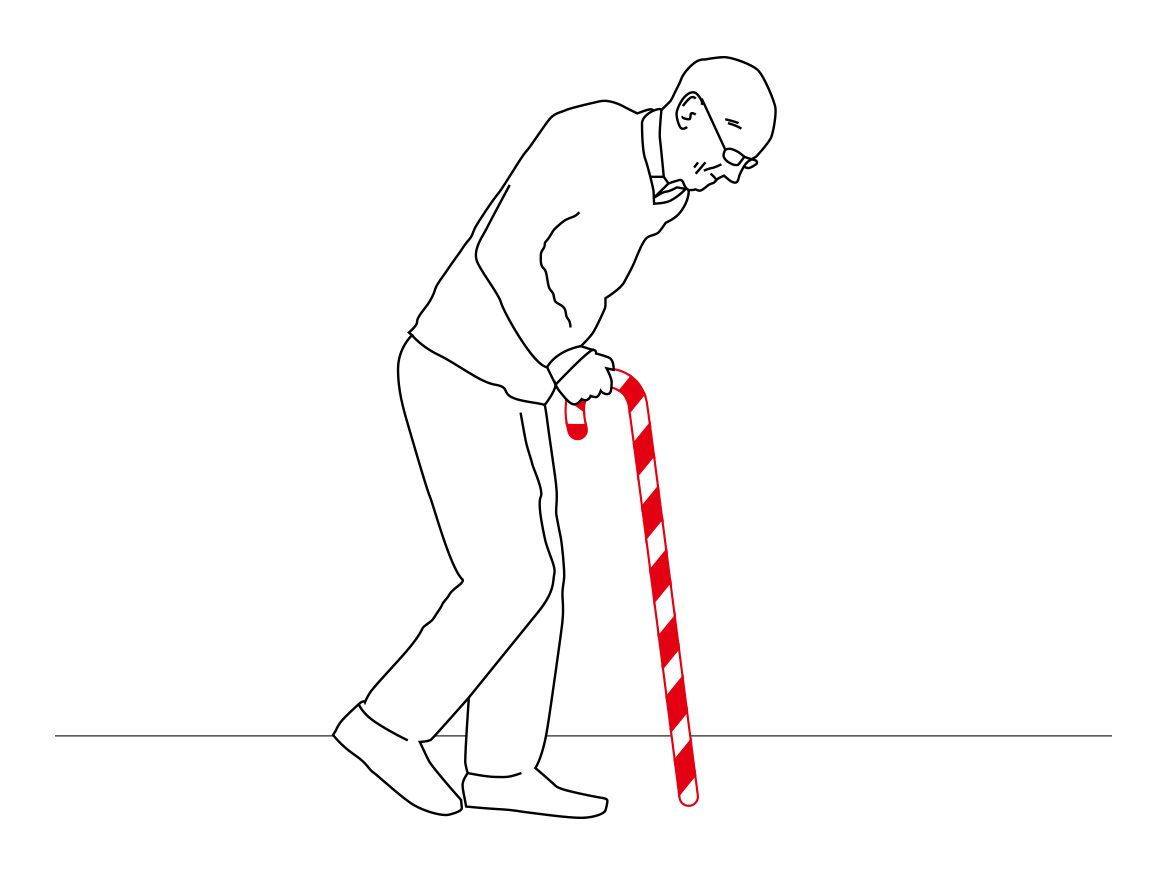

In our research with first time investors, when we asked them to illustrate ‘income’, they drew cash and cheque. When asked to illustrate ‘savings’, they drew a bank branch with its signage. But when they were asked to illustrate a ‘mutual fund’, they drew a blank. But the powerful principles of behavioural science can help create that image for a mutual fund – intuitive and persuasive. Because only if the first time investor gets what a mutual fund is, will she/he trust it and invest in it.