This article first appeared in The Economic Times ET Prime Opinion on 24th November 2021.

In the first quarter of 2021, when Covid-19 cases were relatively low, I asked people in my social circle whether they felt there would be a second wave of the pandemic in India. Everybody I posed the question to said no. It made me wonder what made people feel so sure, even though a second wave had already begun in many other countries, including India, at that point.

Today, when cases are relatively low in India, I’ve been asking the same set of people whether they feel there would be a third wave in India. Almost everybody is once again saying no, even though a third wave has already happened, or is happening in a lot of other countries, especially in Europe.

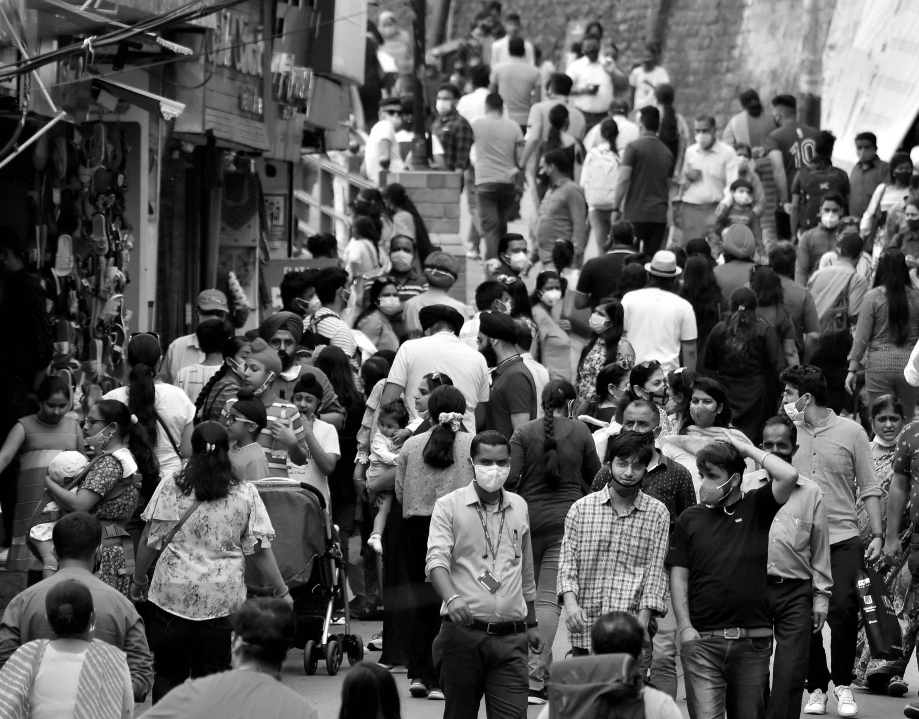

Virologists and epidemiologists have repeatedly warned us (read: are alarmed) about the third wave after Diwali because of the greater likelihood of many people having socialised during the festive season. If you add the current wedding season and factor in that about 75% Indians haven’t been fully vaccinated, the probability of a third wave increases by a large margin.

Even in countries like Britain, where more than two-thirds of the population has been fully vaccinated, a third wave is on, even as severe cases leading to hospitalisations and deaths are down. Yet, most people feel a third wave is not going to happen in India. Why do people perceive risk differently when Covid-19 cases are low as compared to when they are at their peak?

Behavioural science provides an explanation for how we feel when we are in the heat of the moment, compared to how we feel when we in a ‘cold’ condition. If you ask people what they would do when offered a bribe in a ‘cold state’, most people think they will have the will power to resist it. If you ask people on diets, what would they do when offered a delicious chocolate mousse, in the ‘cold state’, most think they will be able to say no.

But, in reality, we feel and act differently in ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ states of mind. In behavioural science, this is known as the ‘hot-cold empathy gap’.

For example, in a 2003 study, ‘Social Projection of Transient Drive States’ (bit.ly/30U7cGU), behavioural scientists Leaf Van Boven and George Loewenstein asked two groups of people that if they were lost in a forest, which would they regret more: not bringing food, or not bringing water? The first group was asked this question just before they started their workout at a gym. 61% said they would regret not bringing water. The second group was asked this question just after their workout at the gym. 92% of this group thought they would regret not bringing water with them in the forest.

After working out, people felt thirstier. This led them to believe that if they were lost in the forest, they would regret not bringing water, because that’s how they felt in the heat of the ‘post-workout’ moment. Far fewer people felt thirsty before the workout, the ‘cold’ state of mind. And, therefore, fewer people chose the water option.

Our behaviour is driven more by our emotional state, less by cold rational thinking. In the heat of the moment, we feel differently than we do when we are ‘cold’ to the situation. There is gap in empathy levels during these ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ emotional states. That’s why after eating a large meal, we can’t imagine being hungry again.

When the stock markets are in a bull run, everything looks rosy, making investors take more risks. People can’t imagine the stock markets crashing. When the stock markets crash, people panic and sell. They can’t imagine it being back up and about again.

Likewise, when Covid-19 cases are low, we are in a ‘cold’ state. We feel the pandemic is over or on its way out. We take more risks. So, even though empirically the third wave is highly likely, we feel it’s unlikely.