This article of ours first appeared in The Hindu on 1st June 2021

The psychology behind trying our luck at booking a vaccine appointment is the same as in gambling.

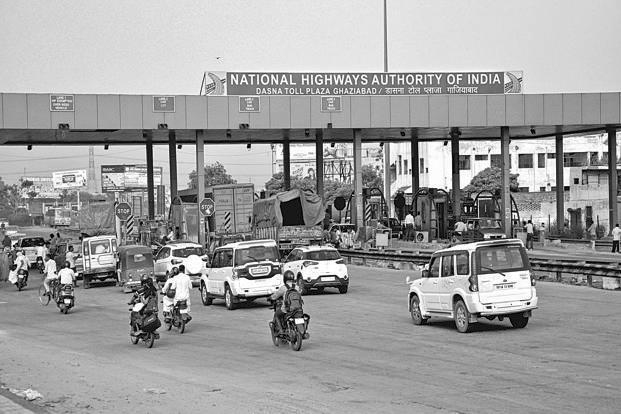

The experience of booking an appointment to get vaccinated in India has been rewarding for some but frustrating for most. The procedure for a citizen to get vaccinated is to register on the Co-WIN website or Aarogya Setu app and schedule an appointment at a preferred centre. It sounds easy until you try it. Soon you realise that no matter how fast you click the confirm button, it’s not easy to get an appointment. That’s because vaccines are in short supply. And that is because the Government of India hasn’t placed enough orders.

People who have been trying to get an appointment find someone or the other in their social network who got lucky with an appointment. That motivates them to keep trying. The system of getting vaccine appointments has become gamified with vaccination centres releasing alerts of slot openings on social media. These alerts inform people about the openings of vaccination slots at any time of the day or night. They keep people hooked on to the game of ‘fastest finger first’ to book an appointment.

Vaccination and gambling

The psychology behind why random alerts and repeated log ins into the website to try one’s luck at booking an appointment works is the same as why people gamble money in casinos or buy lottery tickets. At a casino, people put money in the slot machine and press the button. People don’t know if they’ll win. They can’t predict it. But they believe that the odds of winning increase the more they play. So, they keep gambling. Of course, most people lose more than they win because the odds are always in favour of the casino, which makes most of the money. In the case of trying their luck at getting a vaccination appointment, people eagerly wait for alerts of slot openings, log in and press the confirm button. People don’t know if they’ll ‘win’ an appointment. They can’t predict it. But people believe that the odds of ‘winning’ an appointment increase the more they log in. So, people keep trying. Of course, most people don’t ‘win’ appointments because the odds are not in their favour. The only difference between gambling at casinos and booking vaccination appointments is that in gambling, the casino wins most of the time. But regarding vaccination, both the government and the people lose.

Active conditioning

In Ivan Pavlov’s experiment of classical conditioning, the dogs in the experiment would start drooling when they heard the sounds associated with food preparation. They would drool when the bell rang even though no food was present. After a while, the dogs would stop responding if no food appeared after the bell was rung. But psychologist B. F. Skinner found that rats and pigeons would continue doing the task much longer if they were rewarded occasionally rather than every time. Both are types of conditioning, but Skinner’s conditioning was active, whereas Pavlov’s was passive. The dog didn’t have to do anything conscious to get the reward, whereas the rat and pigeon had to undertake a task. Making the animal take an explicit action produced a stronger, longer lasting effect on behaviour.

Humans respond in similar ways as rats and pigeons when given an occasional reward for repetitive behaviour. Casinos give players the illusion of control by letting players place chips and play their cards. Giving them choices and making people take action makes them feel like they have some control, as opposed to giving purely luck-based unpredictable rewards. In case of vaccinations, the government is giving people the illusion of control by encouraging people to log in and try their luck at booking an appointment. Giving people the choice to take action towards booking an appointment makes people feel like they have some control, even though the odds are highly stacked against ‘winning’ an appointment. There is an element of surprise or uncertainty, so people are never sure when the appointment will come through. This is keeping people engaged. The question is, should the government be operating vaccinations like a casino?