Millions of Indians don’t have access to clean water, sanitation, electricity, education, healthcare, banking. The list can go on. The ones with access to all of it, including myself, are aware of the fact that millions go without it everyday. Yet it hardly moves us to do anything about it.

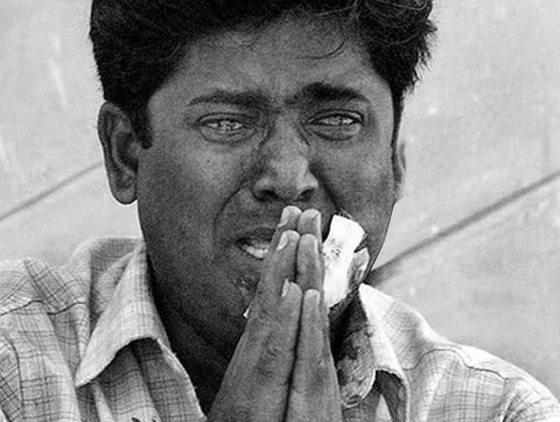

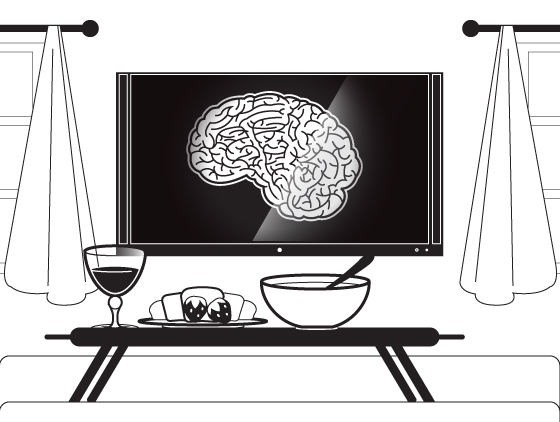

That’s the problem with statistics. It just doesn’t activate our emotions. Paul Slovic, a psychologist at the University of Oregon, has exposed this blind spot in our sympathetic brain. He asked people how much they were willing to donate to various charitable causes. Slovic found that when people were shown a picture of Rokia, a starving Malawian child, with emaciated body and haunting brown eyes, they donated generously to the Save the Children. However, when other people were provided with a list of statistics about starvation throughout Africa – more than 3 million children in Malawi are malnourished, more than 11 million people in Ethiopia need immediate food assistance, and so forth – the donation was 50% lower. At first glance it makes no sense right. When people are informed about the real scope of the problem, they should give more money, not less.

But what happens is that the depressing numbers leave us cold. Our minds can’t comprehend suffering on such a massive scale. That’s why we are riveted when a kid falls in a bore well but turn a blind eye to millions who die every year due to lack of clean drinking water. As Mother Teresa put it, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

Source: Paul Slovic – “If I look at the mass I will never act”: Psychic numbing and genocide – Judgment and Decision Making, vol. 2, no. 2, April 2007, pp. 79-95.