In the preface to his 1960 book ‘Psycho-cybernetics’, Dr Maxwell Maltz, a plastic surgeon turned psychologist wrote:

‘It usually requires a minimum of about 21 days to effect any perceptible change in a mental image. Following plastic surgery it takes about 21 days for the average patient to get used to his new face. When an arm or leg is amputated the “phantom limb” persists for about 21 days. People must live in a new house for about three weeks before it begins to “seem like home”. These, and many other commonly observed phenomena tend to show that it requires a minimum of about 21 days for an old mental image to dissolve and a new one to jell.’

Self-help authors of 21 days to this, that and everything, may have reasoned that, if self-image takes 21 days to change, and self-image changes lead to changes in habits, then habit formation must take 21 days. Although ‘21 days’ may perhaps apply to adjustment to plastic surgery, it is unfounded as a basis for habit formation. Here’s the proof:

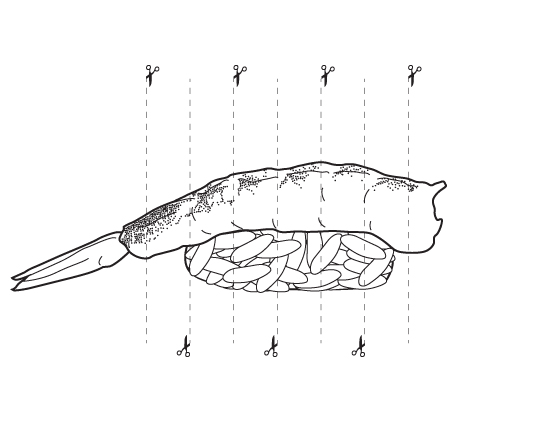

In an 84-day study by researchers at University College London, 96 participants were asked to choose an every day behavior that they wanted to turn into a habit. They all chose something they didn’t already do that could be repeated every day like eating a piece of fruit (behavior) with lunch (cue) or doing 50 sit-ups (behavior) after morning coffee (cue).

So how long did it take to form a habit? On average it took 66 days until a habit was formed. And contrary to what’s commonly believed, missing a day or two didn’t much affect habit formation.

But here is the relevant part. There was considerable variation in how long habits took to form depending on what people tried to do. People who resolved to drink a glass of water after breakfast were up to maximum automaticity after about 20 days, while those trying to eat a piece of fruit after lunch took at least twice as long to turn it into a habit. The exercise habit proves trickiest with 50 sit-ups after morning coffee, still not a habit after 84 days.

Interestingly, there were quite large differences between individuals in how quickly automaticity reached its peak, although everyone repeated their chosen behavior daily: for one person it took just 18 days, and another did not get there in the 84 days, but was forecast to do so after as long as 254 days!

So it’s unwise to attempt to assign a number to habit formation. The duration is likely to differ depending on who you are and what you are trying to do. As long as you continue doing your new healthy behavior consistently in a given situation, a habit will form. But you will probably have to persevere beyond January 21st if you are attempting a New Year’s resolution.

Source: Lally, van Jaarsveld, Potts, & Wardle – How habits are formed: modeling habit formation in the real world – European Journal of Social Psychology 40, no. 6 (2010): 998-1009.